It’s been nine months since we’ve published a WebXPRT 3 browser performance comparison, so we decided to put the newest versions of popular browsers through the paces to see if the performance rankings have changed since our last round of tests.

We used the same laptop as last time: a Dell XPS 13 7930 with an Intel Core i3-10110U processor and 4 GB of RAM running Windows 10 Home, updated to version 1909 (18363.1139). We installed all current Windows updates and tested on a clean system image. After the update process completed, we turned off updates to prevent them from interfering with test runs. We ran WebXPRT 3 three times on five browsers: Brave, Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera. The posted score for each browser is the median of the three test runs.

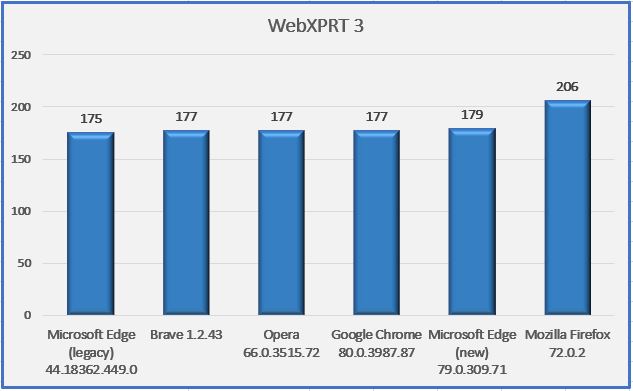

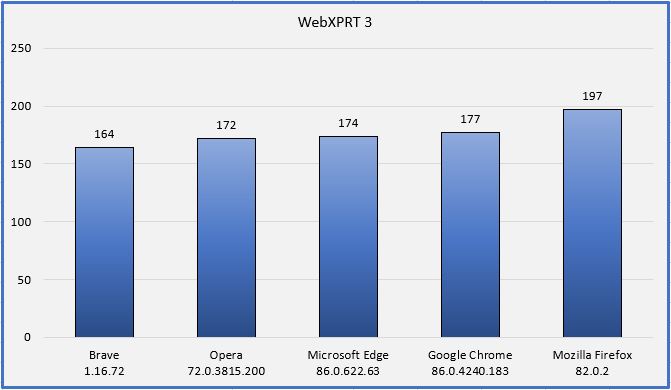

In our last round of tests, the four Chromium-based browsers (Brave, Chrome, Edge, and Opera) produced scores that were nearly identical. Only Mozilla Firefox produced a significantly different (and better) score. The parity of the Chromium-based browsers was not surprising, considering they have the same underlying foundation.

In this round of testing, the Chromium-based browsers again produced very close scores, although Brave’s performance lagged by about 4 percent. Firefox again separated itself from the pack with a higher score. With the exception of Chrome, which produced an identical score as last time, every browser’s score was slightly slower than before. There are many possible reasons for this, including increased overhead in the browsers or changes in Windows, and the respective slowdowns for each browser will probably be unnoticeable to most users during everyday tasks.

Do these results mean that Mozilla Firefox will provide you with a speedier web experience? As we noted in the last comparison, a device with a higher WebXPRT score will probably feel faster during daily use than one with a lower score. For comparisons on the same system, however, the answer depends in part on the types of things you do on the web, how the extensions you’ve installed affect performance, how frequently the browsers issue updates and incorporate new web technologies, and how accurately each browsers’ default installation settings reflect how you would set up that browser for your daily workflow.

In addition, browser speed can increase or decrease significantly after an update, only to swing back in the other direction shortly thereafter. OS-specific optimizations can also affect performance, such as with Edge on Windows 10 and Chrome on Chrome OS. All of these variables are important to keep in mind when considering how browser performance comparison results translate to your everyday experience.

What are your thoughts on browser performance? Let us know!

Justin