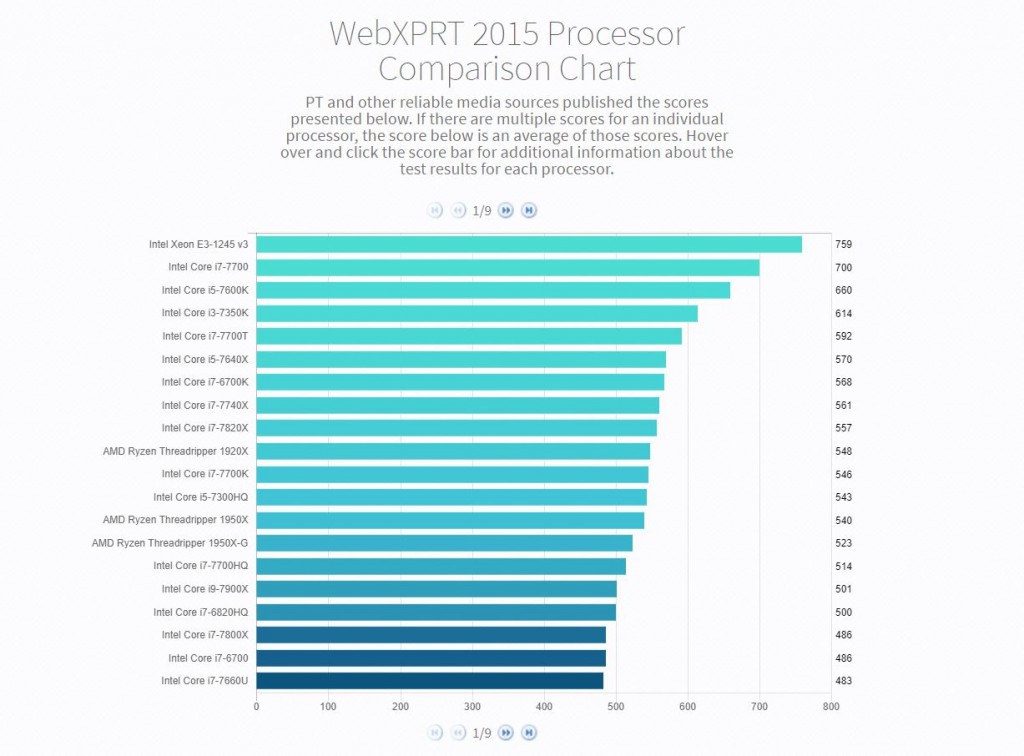

The WebXPRT 2015 Processor Comparison Chart is in its second month, and we’re excited to see that people are browsing the scores. We’re also starting to receive more WebXPRT score submissions for publication, so we thought it would be a good time to describe how that process works.

Unlike sites that publish any results they receive, we hand-select results from internal lab testing, end-of-test user submissions, and reliable tech media sources. In each case, we evaluate whether the score is consistent with general expectations. For sources outside of our lab, that evaluation includes checking to see whether there is enough detailed system information to get a sense of whether the score makes sense. We do this for every score on the WebXPRT results page and the general XPRT results page.

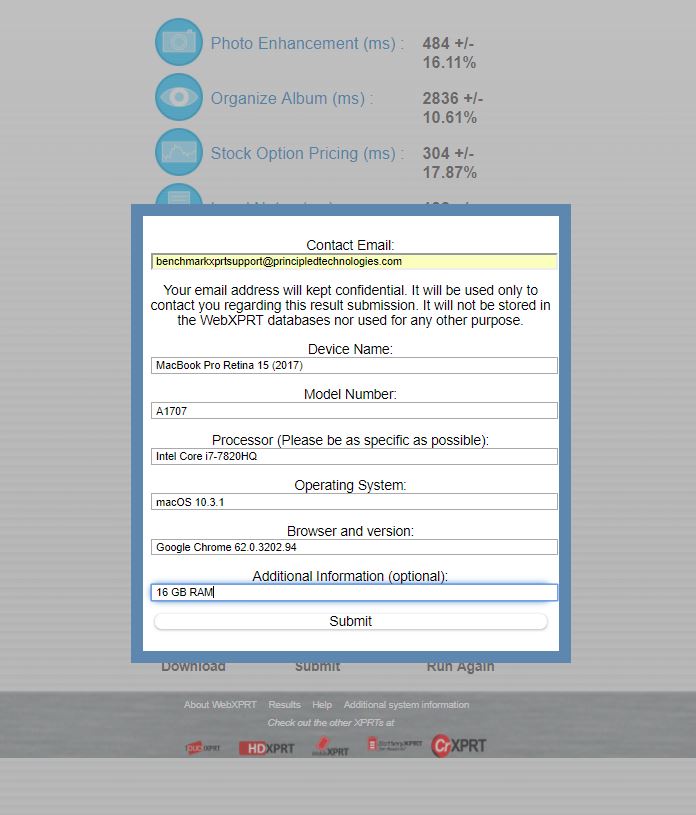

If we decide to publish a WebXPRT result, that score automatically appears in the processor comparison chart as well. If you would like to submit your score, the submission process is quick and easy. At the end of the WebXPRT test run, click the Submit button below the individual workload scores, complete the short submission form, and click Submit again. The screenshot below shows how the form would look if I submitted a score at the end of a WebXPRT run on my personal system.

After you submit your score, we’ll contact you to confirm the name we should display as the source for the data. You can use one of the following:

- Your first and last name

- “Independent tester,” if you wish to remain anonymous

- Your company’s name, provided that you have permission to submit the result in their name. If you want to use a company name, we ask that you provide your work email address.

We will not publish any additional information about you or your company without your permission.

We look forward to seeing your score submissions, and if you have suggestions for the processor chart or any other aspect of the XPRTs, let us know!

Justin